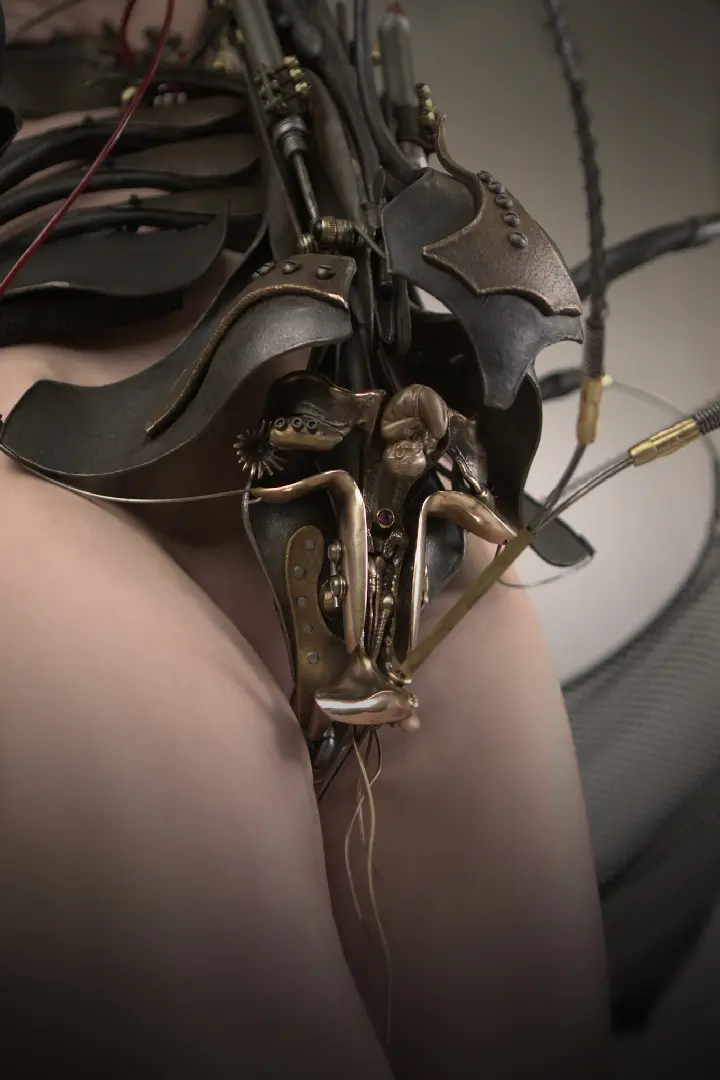

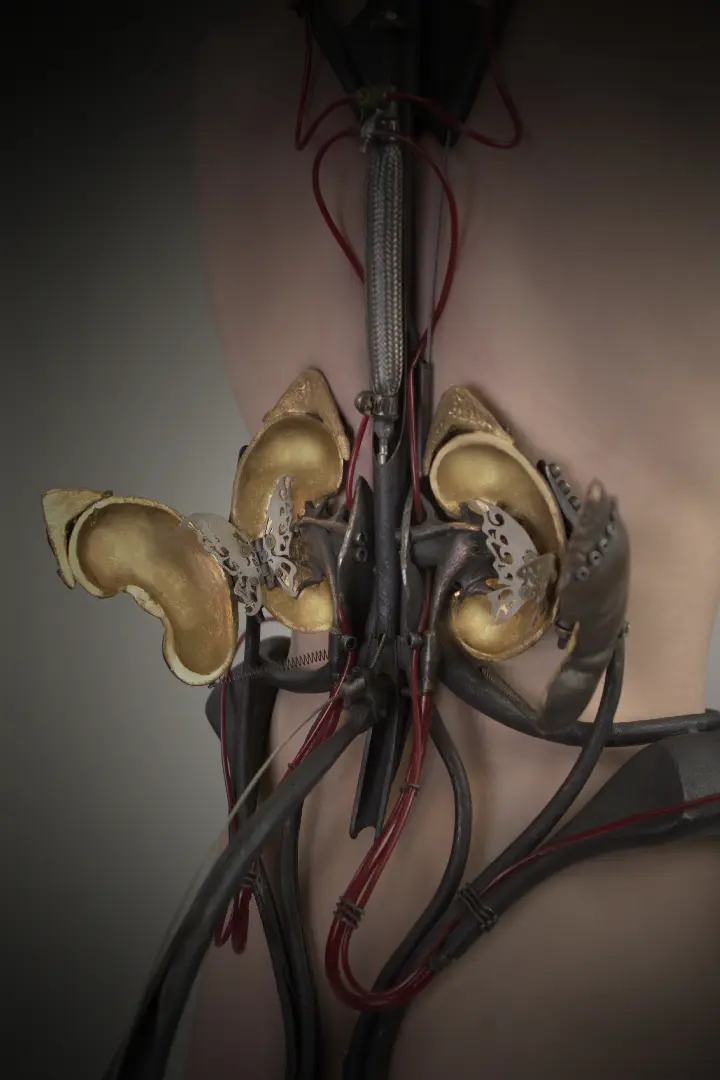

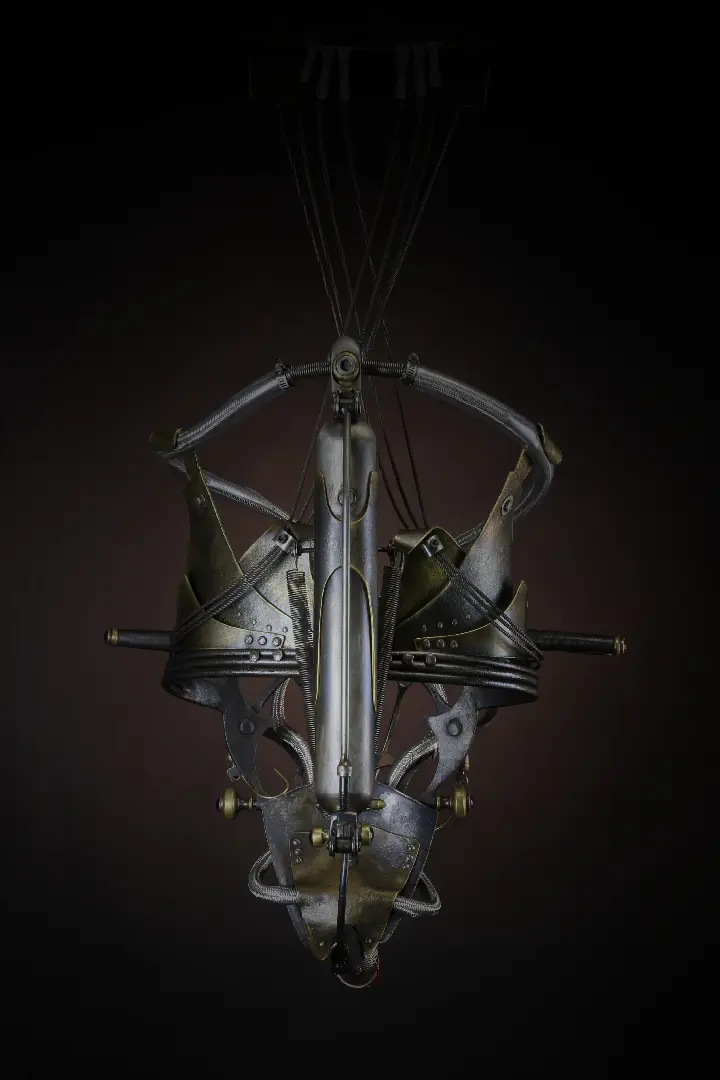

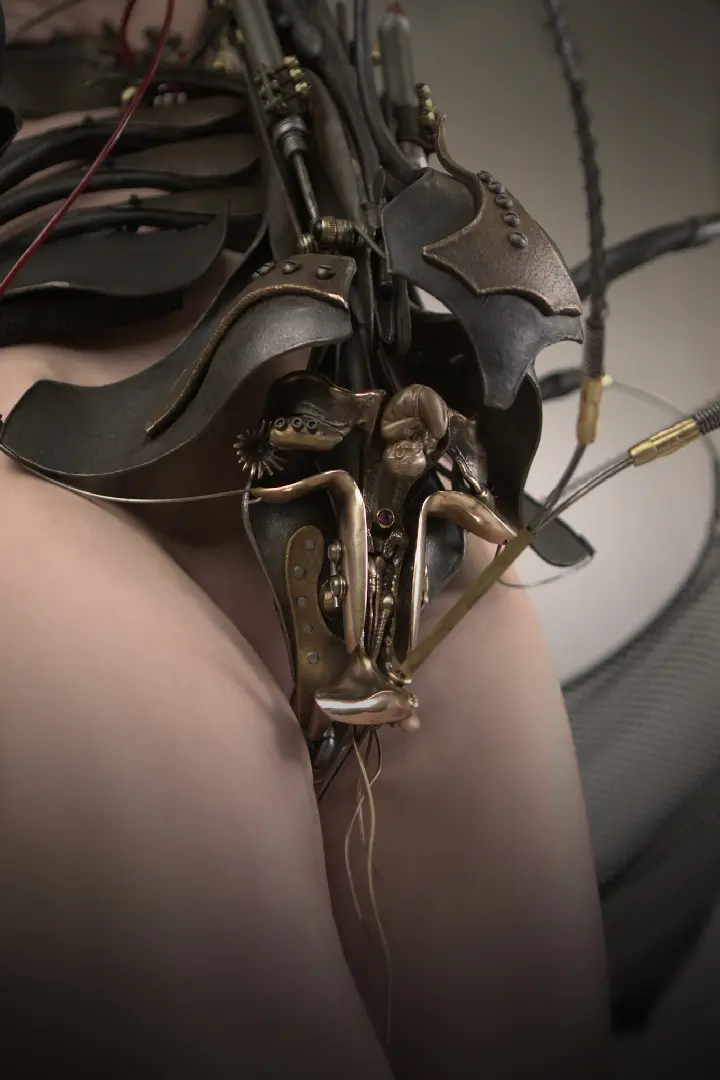

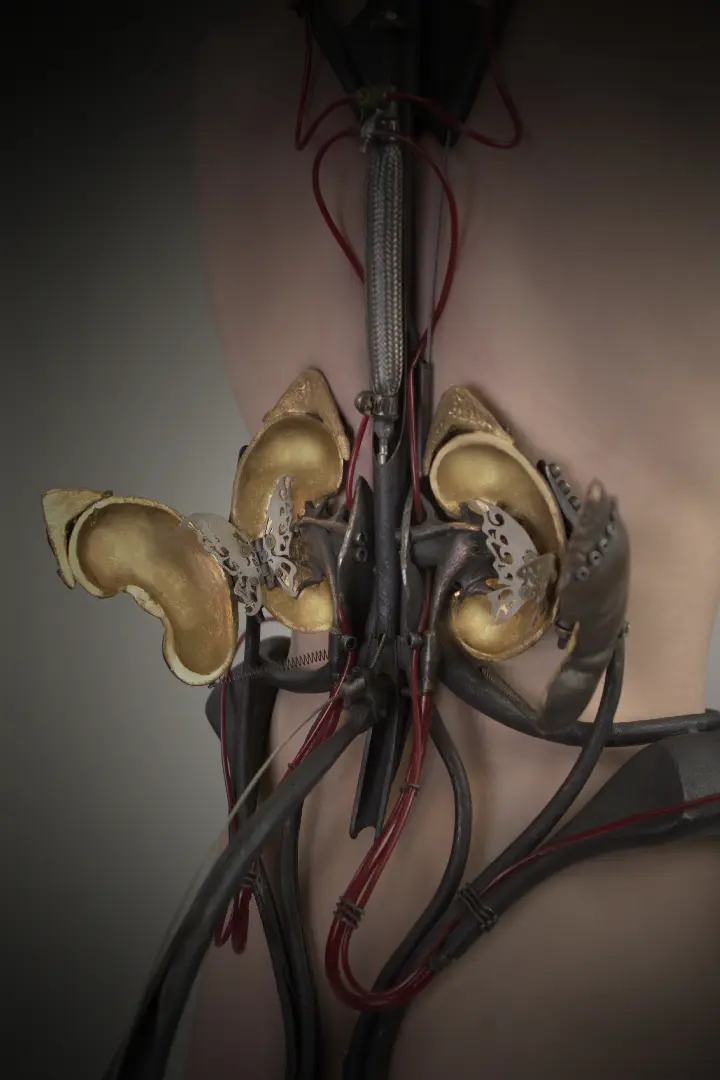

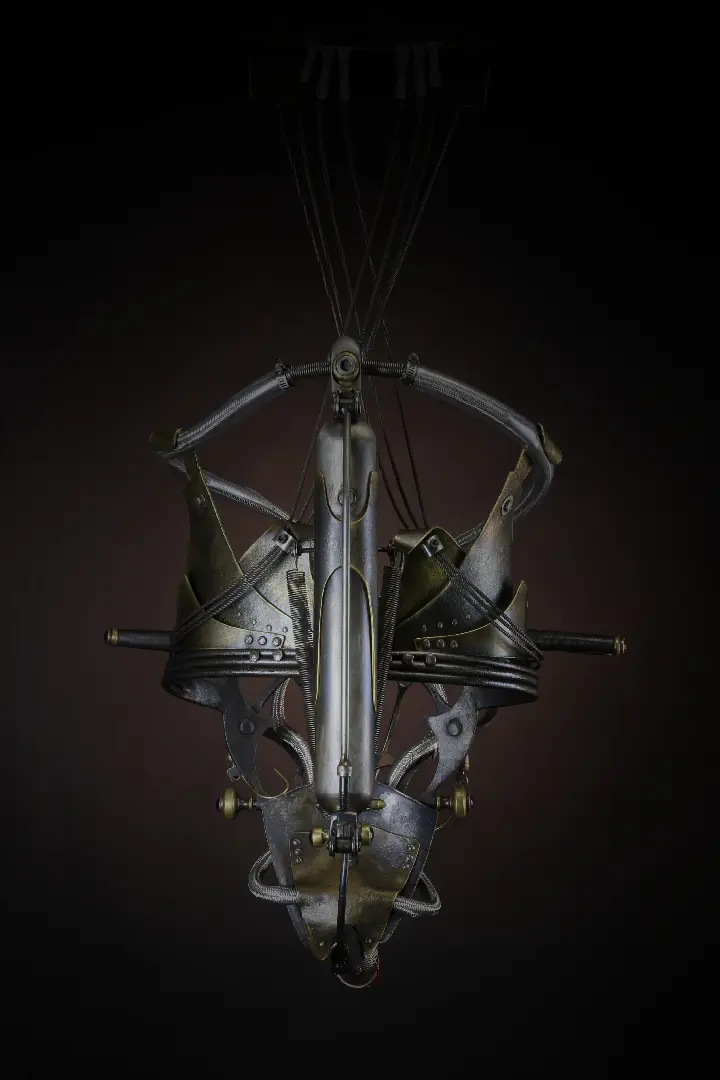

Ira Sherman is an extraordinary artist and metalsmith. He is a master jeweler, internationally recognized sculptor, designer, intuitive engineer and more - a modern metal wizard......

- Elizabeth McDevitt, Metalsmith Magazine

IRA SHERMAN MODERN METAL WIZARD

IRA SHERMAN MODERN METAL WIZARD

Ira Sherman is an extraordinary artist and metalsmith. He is a master jeweler, internationally recognized sculptor, designer, intuitive engineer and more - a modern metal wizard......

- Elizabeth McDevitt, Metalsmith Magazine